In recent summers, the waters off the Baja Peninsula, tremble with thousands upon thousands of wingtips.

The smallest species of Mobula, also known as Munk’s pygmy devil ray, gather in schools by the thousands, one of the largest known aggregations of any elasmobranch in the world. The sheer scale of these events creates a stunning phenomenon as the animals soar in unison just beneath the surface like an aquatic murmuration. But it also creates a precarious moment for the ray population. Despite the prohibition of fishing manta and devil rays in Mexico, these highly mobile animals are highly susceptible to bycatch, unintentionally caught in the massive nets of industrial trawlers or gillnet fishers where they drown before being tossed back into the sea, prohibited product. The elevated risk to an animal known to aggregate en masse makes the question of why they do it all the more important.

The secretive lives of these rays undoubtedly adds to their allure, but it also presents a lot of challenges to understanding more about them. Designing studies to reveal which environmental cues draw the rays together for example, or whether the events are related to reproduction, are critical pieces of their story that could dictate how to protect them, but how does one study an animal that soars where we can’t even breathe? Other mysteries, like why they perform their characteristic aerial stunt breaching the surface before crashing back into the sea, seem almost impossible to confirm without learning to speak to them.

While schools of munkiana appear all around the peninsula and nearby islands, it’s necessary to track individuals to tease out patterns about the groups’ movement, use of habitat, and life cycle. To explore these questions, their movements need to be studied with precision, a feat achieved by tagging rays with small acoustic beacons. As the rays travel the tags reveal their location by emitting a signal picked up by an array of underwater receivers stationed around the region. The challenge of this approach is locating and rounding up the rays as if they were a herd of wild horses, wrangling a portion of the school with a weighted net in order to catch and hold a few long enough to tag and measure. And of course this herd is underwater, fleeing in every direction including down. That’s where the fishermen of Baja California Sur come in.

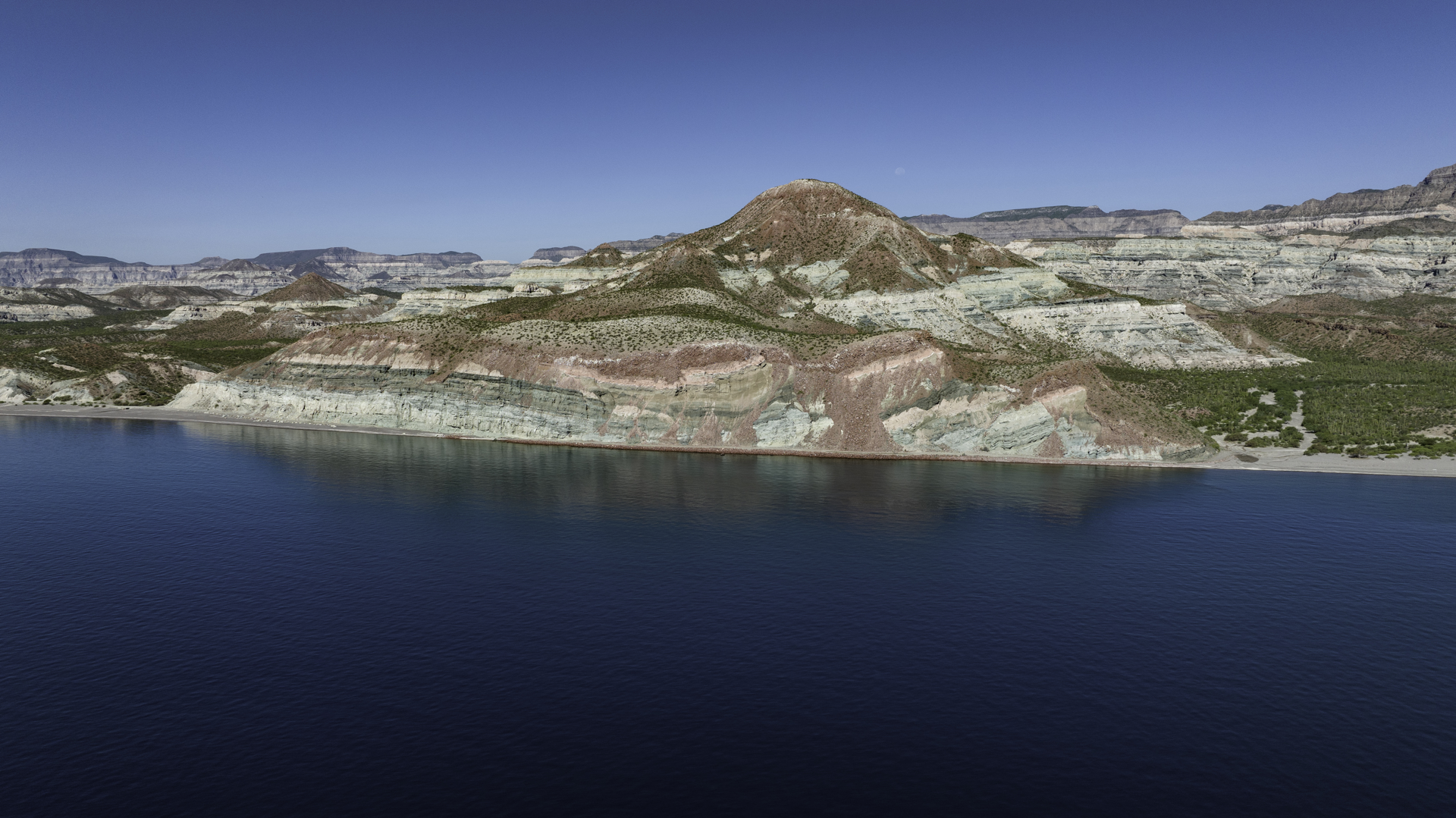

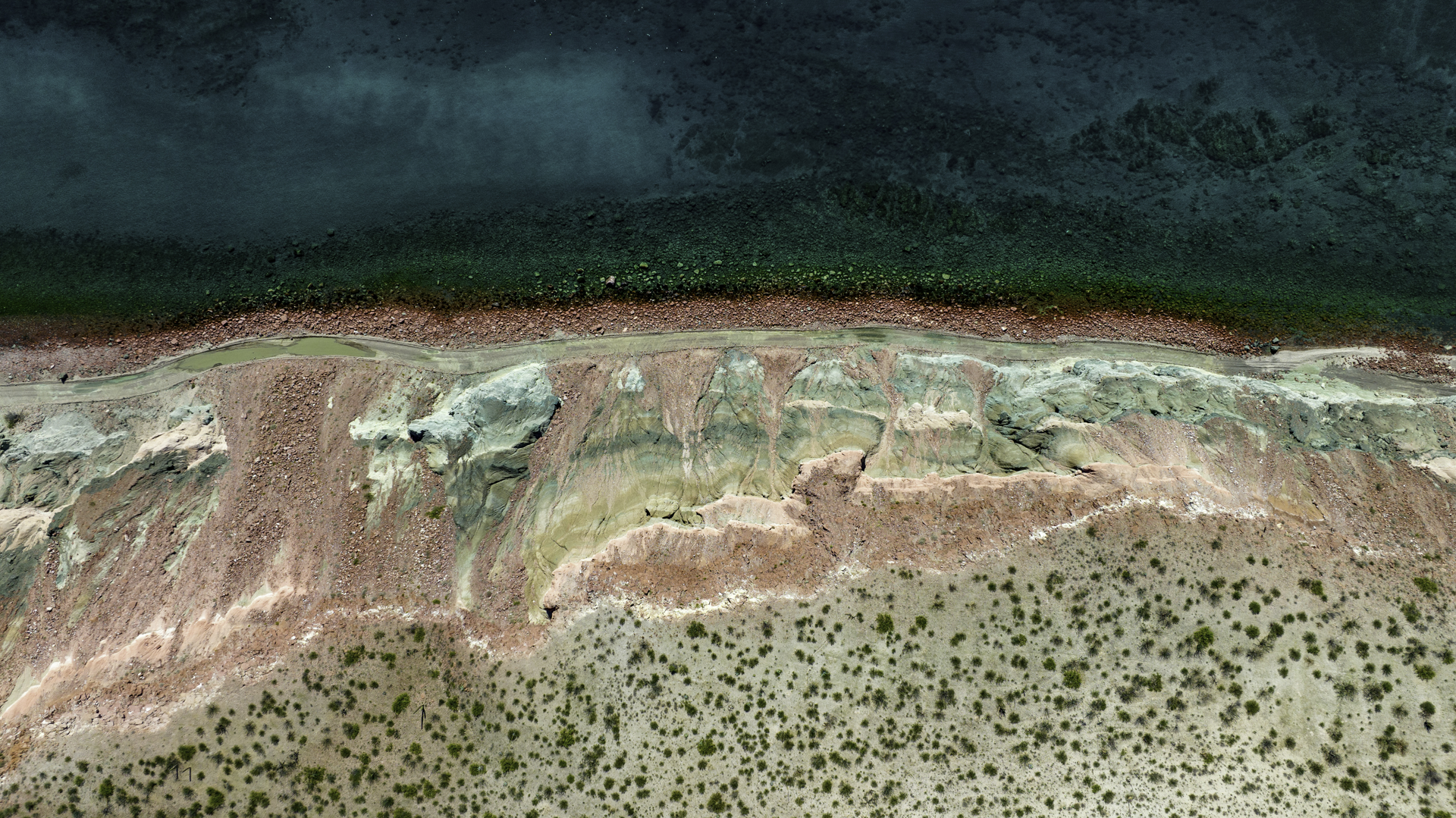

The data that’s been collected so far from tagged mobulas tells the story of how, or at least where, they are spending their time. These rays swim hundreds of kilometers a year, seasonally migrating around the peninsula between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of California. Understanding their full range of movements can inform how we manage activities in these areas that have an impact on this highly vulnerable species.

When researchers and fishers pool their resources, knowledge and capabilities some of the best science is produced. Researchers alone were never going to catch live specimens for tagging, and without this sophisticated tracking system there was no way to confirm movement patterns. The result is a level of capable scientific research that can reveal the ecological importance of very specific areas, an imperative for designing sound management practices or building a case to restrict harmful fishing practices in places of critical importance for life in the sea.